The Romans Most Notable Innovations in Art and Culture Were Found in

Beginnings of Byzantine Art and Architecture

To Start: Defining the Byzantine Catamenia

The term Byzantine is derived from the Byzantine Empire, which adult from the Roman Empire. In 330 the Roman Emperor Constantine established the city of Byzantion in modern day Turkey as the new capital of the Roman empire and renamed information technology Constantinople. Byzantion was originally an ancient Greek colony, and the derivation of the name remains unknown, but nether the Romans the name was Latinized to Byzantium.

In 1555 the German language historian Hieronymus Wolf first used the term Byzantine Empire in Corpus Historiæ Byzantinæ, his collection of the era'south historical documents. The term became popularized among French scholars in the 17th century with the publication of the Byzantine du Louvre (1648) and Historia Byzantina (1680), but was not widely adopted past art historians until the 19th century, as the distinctive style of Byzantine architecture and art in mosaics, icon painting, frescos, illuminated manuscripts, small scale sculptures and enamel piece of work, was divers.

The Byzantine Empire lasted until 1453 when Constantinople was conquered by the Turkish Ottoman Empire. Byzantine art and architecture is usually divided into iii historical periods: the Early on Byzantine from c. 330-730, the Middle Byzantine from c. 843-1204, and Tardily Byzantine from c. 1261-1453. The political, social, and artistic continuity of the Empire was disrupted by the Iconoclastic Controversy from 730-843 and so, again, past the Flow of the Latin Occupation from 1204-1261.

The Roman Empire

In the era leading upwardly to the founding of the Byzantine Empire, the Roman Empire was the well-nigh powerful economic, political, and cultural forcefulness in the world. A polytheistic society, Roman organized religion was securely informed by Greek mythology, as Greek gods were adopted into the Roman mos maiorum, or "way of the ancestors," viewing their ain founding fathers as the source of their identity and worldly power. At the same fourth dimension, as the empire absorbed the deities of the peoples they conquered as a mode of supporting civic stability, the monotheism of Christianity, which starting time appeared in Roman-held Judea in the 1st century, was seen as a political and civil threat. The Emperor Nero instituted the first persecution of Christians, as he blamed the sect for the Swell Fire of Rome in 65, and subsequent emperors followed conform.

In 303 the Roman Emperor Diocletian instituted the Great Prosecution, during an era when political leaders, including Constantine, were engaged in a war, driven by competing claims to be Diocletian's successor. Facing a boxing with his rival Maxentius, fable has it that Constantine converted to Christianity considering of a vision. Described by the historian Eusebius, "he saw with his own optics in the heavens a trophy of the cross arising from the light of the sun, carrying the bulletin, In Hoc Signo Vinces (In this sign, you shall conquer)." Marking his soldier's shields with the Chi Rho, a symbol of Christ, Constantine was victorious and, subsequently, became emperor. His 313 Edict of Milan legalized the practice of Christianity, and in 324, he moved to create a new capital in the Eastward, Constantinople, in order to integrate those provinces into the empire while simultaneously creating a new centre of art, civilization, and learning.

Early Christian Art

Creating frescoes, mosaics, and console paintings, Early Christian art drew upon the styles and motifs of Roman art while repurposing them to Christian subjects. Works of art were created primarily in the Christian catacombs of Rome, where early depictions of Christ portrayed him as the classical "Good Shepherd," a fellow in classical dress in a pastoral setting. At the aforementioned time, meaning was often conveyed by symbols, and an early iconography began to develop. As the Edict of Milan was followed by the Emperor Theophilus I's 380 edict establishing Christianity as the official religion of the empire, Christian churches were congenital and decorated with frescoes and mosaics. The classical sculptural tradition was abandoned, as it was feared that figures in the circular were too reminiscent of pagan idols. In the first two centuries of the Byzantine Empire, as the historians Horst Woldemar Janson and Anthony F. Janson wrote, there was, "No lucent line betwixt Early Christian and Byzantine art. East Roman and West Roman - or, as some scholars adopt to phone call them, Eastern and Western Christian - traits are difficult to separate before the sixth century."

Early Byzantine Fine art and Emperor Justinian I

The flowering of Byzantine architecture and art occurred in the reign of the Emperor Justinian from 527-565, every bit he embarked on a building campaign in Constantinople and, afterwards, Ravenna, Italy. His most notable monument was the Hagia Sophia (537), its name significant "holy wisdom," an immense church building with a massive dome and low-cal filled interior. The Hagia Sophia's many windows, colored marble, bright mosaics, and gold highlights became the standard models for subsequent Byzantine compages.

To pattern the Hagia Sophia, burnt downwards in a previous riot, Justinian I employed two well-known mathematicians, Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles. Isidore taught stereometry, or solid geometry, and physics and was known for compiling the starting time collection of the works of Archimedes, a classical Greek engineer and scientist. A mathematician, Anthemius wrote a pioneering study on solid geometric forms and their relationships while arranging surfaces to focus light on a single bespeak. The two men drew upon their noesis of geometrical principles to engineer the Hagia Sophia's large dome as they pioneered the employ of pendentives. The triangular supports at the corners of the dome's square base redistributed the weight, making information technology possible to build the largest dome in the world until the St. Peter's Basilica dome, which besides employed pendentives, was completed in Rome in 1590.

Hiring 10,000 artisans to build and decorate the Hagia Sophia, Justinian I besides established innumerable workshops in icon painting, ivory carving, enamel metalwork, mosaics and fresco painting in Constantinople. As art historians H.W. Janson and Anthony F. Janson wrote, during his reign, "Constantinople became the artistic equally well as political capital of the empire....The monuments he sponsored have a grandeur that justifies the claim that his era was a golden age." As the Empire was at its virtually geographically expansive during Justinian'due south reign, Byzantine fine art and architecture influenced modern solar day Turkey, Greece, the Adriatic regions of Italy, the Centre East, Espana, Northern Africa, and Eastern Europe. While other structures, particularly his Chrysotriklinos, the imperial palace reception room, were equally influential, that edifice, similar other early structures in Constantinople, was later on destroyed. As a result, the best examples of Early on Byzantine innovation can exist seen in Ravenna, Italia.

Ravenna, Italia

Justinian I appointed his protégé Maximianus, a lowly and somewhat unpopular deacon, every bit Archbishop of Ravenna, where he acted as a kind of implicit regent for the Emperor inside Italian republic. In 547, Maximianus completed the construction of San Vitale, a central-program church using a Greek cantankerous inside a square that became a model for subsequent architecture. The shallow dome, placed upon a drum, used terra cotta forms for the beginning fourth dimension equally construction material, while the interior's exquisite mosaics and sacred objects, including the Throne of Maximianan (mid-xith century) defined the Byzantine style.

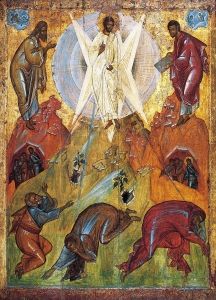

Having survived almost intact since its consecration, the interior of the Church of San Vitale created an effect of intricate splendor, with every inch richly decorated. Large mosaics depicting the Emperor and Empress established Byzantine composition and figurative techniques, as the realistic depictions of classical art were abased in favor of an emphasis upon iconographic formality. The tall, thin, and motionless figures with almond shaped faces and wide eyes, posed frontally, against a aureate groundwork became the instantly recognizable definition of Byzantine art.

Acheiropoieta and Icons

Early Byzantine artists pioneered icon painting, small panels depicting Christ, the Madonna, and other religious figures. Objects of both personal and public veneration, they developed from classical Greek and Roman portrait panels and were informed by the Christian tradition of Acheiropoieta. Acheiropoieta, pregnant, "made without hands," was an epitome believed to have been miraculously created. According to tradition, St. Luke the Evangelist, one of the original twelve apostles, painted the paradigm of the Madonna and Child Jesus when they miraculously appeared to him. The Monastery of the Panaghia Hodegetria in Constantinople was built to house a at present-lost icon believed to be St. Luke's painting. As art historian Robin Cormack noted, it became "perchance the most prominent cult object in Byzantium." These miraculous images influenced the development of iconographic types, every bit St. Luke's icon became known equally Hodegetria, meaning "She Who Points the Way," as the Madonna pointed to the Child Jesus.

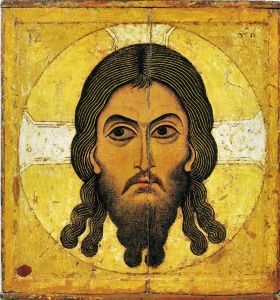

Acheiropoieta were often credited with contemporary miracles. The Epitome of Edessa was believed to take come to the divine aid of the urban center of Edessa in its 593 defense against the Persians. The central image of Christ's head, known every bit the Mandylion in the Byzantine tradition, recalled the image of Christ's face imprinted on a cloth while he walked to the place of his crucifixion. Worshippers believed they were in the presence of the divine, as art historian Elena Boerck wrote, "Icons, unlike idols, have their own agency. They're interactive images, in which the divine is present." Nonetheless, as the worship of icons became a ascendant feature of Byzantine life, a vehement and destructive theological debate developed.

Iconoclastic Controversy

By the viiith century, the Byzantine Empire was under pressure and oftentimes at war, and in this tense climate the controversy over the spiritual validity of icons erupted. Motivated past the belief that contempo events, including military defeats and a volcanic eruption in the Aegean Body of water in 726, were God's punishment for what he chosen, "a arts and crafts of idolatry," the Emperor Leo 3 officially prohibited religious images in 730 and launched a movement chosen Iconoclasm, meaning "breaking of icons." Long standing theological debates over the divine and human nature of Christ and a power struggle between the majestic state and the church stoked the controversy. The Iconoclasts felt that no icon could portray both Christ's divine and homo nature, and to convey only i aspect of Christ was a heresy. Those who supported icons argued that, different idols which depicted a false god, the images merely depicted the incarnate Christ and that the images derived their potency from Acheiropoieta. By inserting himself into the debate, the Emperor substituted royal prescript for religious potency, undercutting the influence and power of the church building. Later, the state violently supressed monastic clergy and destroyed icons.

th century), portrayed Byzantine Empress Theodora and her son Michael III as the Hodegetria, a Madonna and Child icon presiding over the restoration of icons." data-initial-src="/images20/photo/photo_byzantine_art_8.jpg" width="235" height="300" src="https://www.theartstory.org/images20/photo/photo_byzantine_art_8.jpg">

th century), portrayed Byzantine Empress Theodora and her son Michael III as the Hodegetria, a Madonna and Child icon presiding over the restoration of icons." data-initial-src="/images20/photo/photo_byzantine_art_8.jpg" width="235" height="300" src="https://www.theartstory.org/images20/photo/photo_byzantine_art_8.jpg">

The era came to an end with a change in imperial power. Post-obit the expiry of her hubby, the Emperor Theophilus, in 842, the Empress Theodora took the throne and, equally she was passionately devoted to the veneration of icons, summoned a council that restored icon worship and deposed the iconoclastic clergy. The occasion was celebrated at the Banquet of Orthodoxy in 843, and icons were carried in triumphal procession back to the various churches from which they had been taken. Nonetheless, the Iconoclastic Controversy had a notable impact on the later evolution of art, as the councils that restored the worship of icons also formulated a codified system of symbols and iconographic types that were also followed in mosaics and fresco painting.

Middle Byzantine 867-1204

The Middle Byzantine era is often called the Macedonian Renaissance, as Basil I the Macedonian, crowned in 867, reopened the universities and promoted literature and art, renewing an interest in classical Greek scholarship and aesthetics. Greek was established as the official language of the Empire, and libraries and scholars compiled extensive collections of classical texts. The Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, Photios was not only the leading theologian but has been described by the historian Adrian Forescue as "the greatest scholar of his time." His Bibliotheca was an important compilation of almost three hundred works by classical authors, and he played a leading function in seeing Byzantine civilization as rooted in Greek culture. The upshot was, as Janson and Janson wrote, "an virtually antiquarian enthusiasm for the traditions of classical art," displayed in works similar the illuminated manuscript, the Paris Psalter (c. 900) a volume of Biblical psalms that included full page illustrations from the life of Male monarch David and that employed a more than realistic treatment of both the figures and the mural.

Throughout Europe, Byzantine culture and art was seen equally the height of artful refinement, and, as a result, many rulers, even those politically antagonistic to the Empire, employed Byzantine artists. In Sicily, which had been conquered by the Normans, Roger II, the first Norman King, recruited Byzantine artists and, as a effect, the Norman architecture that developed in Sicily and Great Britain, post-obit the Norman Conquest in 1066, greatly influenced Gothic architecture. Hundreds of Byzantine artists were also employed at the Basilica of San Marco in Venice when structure began in 1063. In Russian federation, Vladimir of Kiev converted to the Orthodox Church building upon his wedlock to a Byzantine princess. He employed artists from Constantinople at the St. Sophia'south Cathedral he built in Kiev in 1307. Notable examples of Macedonian Renaissance art were besides created in Hellenic republic, while the influx of Byzantine artists influenced art throughout Western Europe as shown by the Italian artist Berlinghiero of Lucca's Hodegetria (c. 1230).

The Latin Occupation 1204-1261

Famed for its wealth and creative treasures, Constantinople was cruelly sacked and the Empire conquered in 1204 past the Crusade Ground forces and Venetian forces under the Fourth Crusade. The brutal attack upon a Christian urban center and its inhabitants was unprecedented, and historians view it as a turning point in medieval history, creating a lasting schism betwixt the Catholic and Orthodox churches, severely weakening the Byzantine Empire and contributing to its afterwards demise when conquered by the Turkish Ottoman Empire. Many notable artworks and sacred objects were looted, destroyed, or lost. Some works, like the Roman bronze works of the Hippodrome, were carried off to Venice where they are still on display, while other works, including sacred objects and altars also as classical bronze statues, were melted down, and the Library of Constantinople was destroyed. Though the Latins were driven out by 1261, Byzantium never recovered its former celebrity or power.

Late Byzantium 1261-1453

Following the Latin Conquest, the Tardily Byzantine era began to renovate and restore Orthodox churches. However, equally the Conquest had decimated the economy and left much of the city in ruins, artists employed more economical materials, and miniature mosaic icons became popular. In icon painting, the suffering of the population during the Conquest led to an emphasis upon images of compassion, as shown in sufferings of Christ. Artistic vitality shifted to Russia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Hellenic republic, where regional variations of icon painting adult. Russia became a leading heart with the Novgorod School of Icon Painting, led by master painters Theophanes the Greek and Andrei Rublev. Byzantine fine art likewise influenced contemporaneous art in the Due west, particularly the Sienese School of Painting and the International Gothic Style, as well equally painters like Duccio in his Stroganoff Madonna (1300).

Byzantine Art and Architecture: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Architectural Innovations

Known for its central plan buildings with domed roofs, Byzantine architecture employed a number of innovations, including the squinch and the pendentive. The squinch used an arch at the corners to transform a square base into an octagonal shape, while the pendentive employed a corner triangular back up that curved up into the dome. The original architectural design of many Byzantine churches was a Greek cantankerous, having four arms of equal length, placed within a square. Later, peripheral structures, like a side chapel or 2d narthex, were added to the more traditional church footprint. In the xithursday century, the quincunx building design, which used the four corners and a fifth element elevated above it, became prominent as seen in The Holy Apostles in Thessaloniki, Athens, Greece. In addition to the cardinal dome, Byzantine churches began calculation smaller domes around information technology.

Poikilia

Byzantine architecture was informed past Poikilia, a Greek term, significant "marked with various colors," or "variegated," that in Greek aesthetic philosophy was adult to suggest how a complex and diverse assemblage of elements created a polysensory feel. Byzantine interiors, and the placement of objects and elements inside an interior, were designed to create e'er changing and animated interior as light revealed the variations in surfaces and colors. Variegated elements were likewise achieved by other techniques such equally the employment of bands or areas of gold and elaborately carved stone surfaces.

For instance the basket capitals in the Hagia Sophia were then intricately carved, the stone seemed to dematerialize in calorie-free and shadow. Decorative bands replaced moldings and cornices, in outcome rounding the interior angles so that images seemed to flow from 1 surface to another. Photios described this surface upshot in one of his homilies: "It is as if 1 had entered heaven itself with no i barring the fashion from any side, and was illuminated by the beauty in changing forms...shining all around like so many stars, so is one utterly amazed. [...] Information technology seems that everything is in ecstatic movement, and the church building itself is circumvoluted around."

Iconographic Types and Iconostasis

Byzantine art developed iconographic types that were employed in icons, mosaics, and frescoes and influenced Western depictions of sacred subjects. The early on Pantocrator, meaning "all-powerful," portrayed Christ in majesty, his right manus raised in a gesture of didactics and led to the development of the Deësis, pregnant "prayer," showing Christ as Pantocrator with St. John the Baptist and the Virgin Mary, and, sometimes, additional saints, on either side of him. The Hodegetria developed into the subsequently iconographic types of the Eleusa, meaning tenderness, which showed the Madonna and the Child Jesus in a moment of affectionate tenderness, and the Pelagonitissa, or playing child, icon. Other iconographic types included the Homo of Sorrows, which focused on depicting Christ's suffering, and the Anastasis, which showed Christ rescuing Adam and Eve from hell. These types became widely influential and were employed in Western art as well, though some like the Anastasis merely depicted in the Byzantine Orthodox tradition.

Iconostasis, meaning "altar stand," was a term used to refer to a wall composed of icons that separated worshippers from the altar. In the Centre Byzantine catamenia, the Iconostasis evolved from the Early Byzantine templon, a metal screen that sometimes was hung with icons, to a wooden wall equanimous of panels of icons. Containing three doors that had a hierarchal purpose, reserved for deacons or church notables, the wall extended from floor to ceiling, though leaving a space at the top then that worshippers could hear the liturgy around the altar. Some of the most noted Iconostases were developed in the Late Byzantine period in the Slavic countries, as shown in Theophanes the Greek's Iconostasis (1405) in the Cathedral of the Proclamation in Moscow. A codified system governed the placement of the icons arranged according to their religious importance.

Novgorod Schoolhouse of Icon Painting

The Novgorod Schoolhouse of Icon Painting, founded by the Byzantine creative person, Theophanes the Greek, became the leading school of the Tardily Byzantine era, its influence lasting across the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453. Theophanes' work was known for its dynamic vigor due to his brushwork and his inclusion of more than dramatic scenes in icons, which were unremarkably merely depicted in big-scale works. He is believed to have taught Andrei Rublev who became the most renowned icon painter of the era, famous for his ability to convey complex religious thought and feeling in subtly colored and emotionally evocative scenes. In the next generation, the leading icon painter Dionysius experimented with balance betwixt horizontal and vertical lines to create a more dramatic effect. Influenced by Early Renaissance Italian artists who had arrived in Moscow, his style, known for pure color and elongated figures, is sometimes referred to equally "Muscovite mannerism," as seen in his icon serial for the Cathedral of the Dormition (1481) in Moscow.

Carved Ivory

In the Byzantine era, the sculptural tradition of Rome and Greece was essentially abandoned, equally the Byzantine church felt that sculpture in the round would evoke pagan idols; however, Byzantine artists pioneered relief sculpture in ivory, usually presented in small portable objects and common objects. An early case is the Throne of Maximianan (also chosen, the Throne of Maximianus), made in Constantinople for the Archbishop Maximianus of Ravenna for the dedication of San Vitale. The work depicted Biblical stories and figures, surrounded past decorative panels, carved in dissimilar depths so that the almost 3-dimensional handling in some panels contrasted against the more shallow 2-dimensional treatment of others.

In the Heart Byzantine menstruation, ivory carving was known for its elegant and delicate detail, as seen in the Harbaville Triptych (mid-11th century). Reflecting the Macedonian Renaissance's renewed interest in classical art, artists depicted figures with more naturally flowing draperies and contrapposto poses. Byzantine ivory carvings were highly valued in the West, and, equally, a outcome, the works exerted an artistic influence. The Italian artist Cimabue'south Madonna Enthroned (1280-90), a work prefiguring the Italian Early Renaissance's utilize of depth and space, is predominantly informed by Byzantine conventions.

Later Developments - Subsequently Byzantine Fine art and Architecture

During its about 1000 year bridge, the Byzantine era influenced Islamic architecture, the fine art and compages of the Carolingian Renaissance, Norman architecture, Gothic compages, and the International Gothic style. When the Turkish Ottoman Empire conquered Constantinople in 1453, renaming it Istanbul, the Byzantine Empire came to an end. Nonetheless the Byzantine manner continued to be employed in Greece and in Eastern Europe and Russia, where a "Russo-Byzantine" style developed in architecture.

In the mid-1800s, Russia underwent a Byzantine Revival, besides called the Neo-Byzantine, which was established as the official style for churches by Alexander Ii of Russia, who reigned from 1885-1891. The manner continued to be used until Earth War I, and, following the Russian Revolution of 1917, a number of architects immigrated to the Balkans where churches in the Byzantine Revival style continued to be made until afterward World State of war II. The veneration of icons, and the painting of them, is notwithstanding a notable characteristic of the Orthodox faith, as Orthodox households have a space dedicated to icons, and churches, renowned for their images, depict worshippers from near and far.

Byzantine icons have continued to exert an influence, being employed for more than traditional religious imagery, such as Luigi Crosio'due south late 19th-century rendering of Lady of Refuge, a popular paradigm amongst Catholics, simply besides reframed inside modern art in works such equally Natalia Goncharova's The Evangelists (1911) and other Russian Futurists of the fourth dimension. In particular, Russian Suprematist painter Kazimir Malevich famously exhibited his radically abstruse Black Square (1915) in the corner of the room, a infinite traditionally reserved for religious icons and referred to as the "cherry corner." As Russian writer Tatyana Tolstaya wrote of this radical act, "Instead of red, black (zero colour); instead of a face, a hollow recess (naught lines); instead of an icon - that is, instead of a window into the heavens, into the light, into eternal life - gloom, a cellar, a trapdoor into the underworld, eternal darkness." In subverting the traditional Byzantine icon, Malevich hoped to annotate on the dour land of modernity.

Contemporary Interpretations of the Style

Contemporary artists working in Byzantine styles and subjects include the Russian Proverb Sheshukov, the Romanian Ioan Pope, the American architect Andrew Gould, iconographer Peter Pearson, the Canadian sculptor Jonathan Pageau, and the Ukrainian Angelika Artemenko. The Archimandrite, or priest-monk, Zenon Theodor was acclaimed for his 2008 paintings in St. Nicholas Cathedral, in Vienna, Austria, while Greek creative person Fikos combines Byzantine murals and icons with his interest in street art, comic book strips, and graffiti in what he calls "Gimmicky Byzantine Painting." In America, the Brooklyn-based Alfonse Borysewicz has been called "one of the most of import religious artists since the French Catholic Georges Rouault" past fine art historian Gregory Wolfe.

arbucklepironerts.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theartstory.org/movement/byzantine-art/history-and-concepts/

0 Response to "The Romans Most Notable Innovations in Art and Culture Were Found in"

Post a Comment